Our Region

Our Watershed and its Estuaries are truly special places

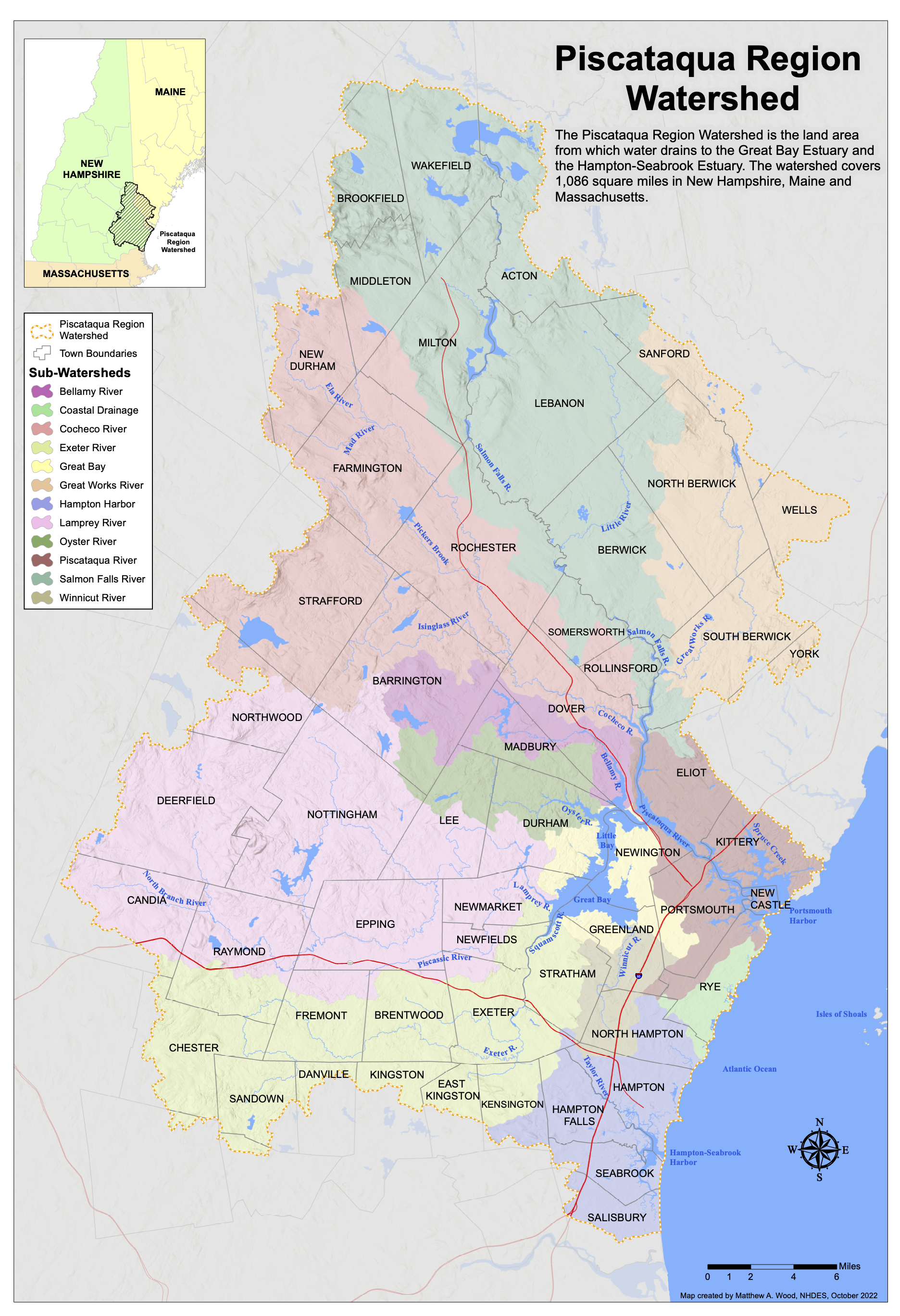

Piscataqua Region Watershed

A watershed is an area of land where all the water from rain and snow drains into a common body of water, like a river, bay, or ocean. Our waterways are deeply connected, even if they are miles apart. From Wakefield, New Hampshire to Kittery, Maine, our watershed is like a big bowl that catches all the water and channels it to one place: the ocean.

The Piscataqua Region Watershed spans 52 cities and towns (42 in New Hampshire and 10 in Maine) that drain to the Piscataqua River, Hampton-Seabrook Estuary, or the Atlantic Ocean. The water in our 1,086 square mile watershed connects us all, from headwaters* to our estuaries in Great Bay and Hampton-Seabrook.

Click on the map to the right to see a larger picture of our watershed.

*Headwaters are the starting points of rivers or streams, often found in small creeks, ponds, or lakes high up in a watershed.

Our Estuaries

An estuary is a place where fresh and saltwater meet and mix together. These diverse ecosystems are places we fish, swim, kayak, birdwatch, or simply walk along a marshy shoreline. Estuaries are homes to nature and people alike. As natural nurseries, they provide homes for diverse marine life like lobsters, fish, oysters and seagrass, as well as passage for migratory fish. For people, they offer recreational opportunities and inspire a deep connection to nature. Estuaries also play a vital role in protecting communities from storms and floods, making them a critical part of both ecological and human life. In our watershed, Great Bay and Hampton-Seabrook are two nationally significant estuaries.

Critical Species

The critical species that have been identified as important to our estuaries include soft-shell clams, American oysters, Eastern brook trout, migratory fish, shorebirds, salt marsh breeding birds, and eelgrass. Robust populations of these species are good indicators of estuarine, marsh, and watershed health. Learn about each of these species below.

- Primarily found in the Hampton-Seabrook Estuary, although they exist in the Great Bay Estuary as well.

- An important economic, recreational, cultural, and natural resource for the Seacoast region.

- Recreational shellfishing in the Hampton-Seabrook Estuary is estimated to contribute more than $3 million a year to the New Hampshire economy.

- Predators (primarily green crabs), disease, and recreational harvest pressures have caused the clam populations to decline.

- Periodically, harvesting is limited by the presence of red tide toxins and high bacteria counts.

For the latest information about clams and shellfish harvest opportunities, check out the Clams Indicator in the State of Our Estuaries report.

Critical Habitats

Habitats that are critical to the health of our estuaries include freshwater wetlands, streams, eelgrass beds, oyster reefs, and salt marshes. These habitats are threatened by increasing population, declining water quality, invasive species encroachment by development, and climate change. Learn about each of these species below.

- Freshwater wetlands store large quantities of water and provide habitat and food for many wildlife species.

- They provide a storage basin for rain, snow, and runoff and can be effective at removing pollutants and maintaining clean water.

- Water from wetlands is slowly released into streams and rivers and helps sustain these systems in periods of low flow and acts as sponges in periods of flood protecting people and property.

- While land protection or local regulations protect some wetland systems from encroaching development, filling, and associated degradation, most wetlands remain vulnerable.

- Polluted stormwater runoff from developed areas adjacent to wetlands can negatively impact the hydrology, plant community, and habitat value of freshwater wetlands.

Critical Issues

Our estuaries – and their surrounding landscapes – are impacted directly and indirectly by several stressors. Some of these are slow-acting and chronic while others are episodic. These influences, however, act as stressors and cannot be considered independently of one another. Learn about each of these species below or check out the "Big Picture" section of the State of Our Estuaries report.

- Our region is experiencing changing precipitation and more extreme storm events.

- Between 2004 and 2009, total annual precipitation levels remained above the 75th percentile.

- Since 2012, levels have been below the 25th percentile.

- Between 1996 and 2014, extreme precipitation (two inches or more in one day) in the Northeast was 53% higher than it was in the previous 94 years.

- The 2006 Mother’s Day Storm alone greatly increased levels of dissolved organic matter and brought salinity levels close to zero for five days.